COOL STUFF FROM LIBRARY BOOKS, Entry #10

"Billy Sunday, UNSHACKLED!"

"Billy Sunday, UNSHACKLED!"

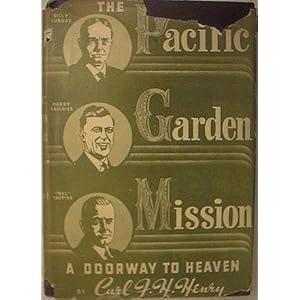

From: "THE PACIFIC GARDEN MISSION

A Doorway to Heaven"

By Carl F. H. Henry

Copyright @ 1942

A Doorway to Heaven"

By Carl F. H. Henry

Copyright @ 1942

CHAPTER SIX

LOADING THE BASES ON THE SAWDUST TRAIL

Billy Sunday never saw his father who walked thirty miles to enlist in the Civil War and died

with scores of other Iowa infantrymen after fording a partly frozen river. From the front lines he

had written the expectant mother, “If it is a boy, name him William Ashley.” Mother and

children lived in the Ames, Iowa, log cabin for years before they managed to move into a frame

house. Perhaps that accounted for Billy Sunday’s illness the first three years of his life, which an

itinerant doctor cured with a syrup stewed from wild roots.

with scores of other Iowa infantrymen after fording a partly frozen river. From the front lines he

had written the expectant mother, “If it is a boy, name him William Ashley.” Mother and

children lived in the Ames, Iowa, log cabin for years before they managed to move into a frame

house. Perhaps that accounted for Billy Sunday’s illness the first three years of his life, which an

itinerant doctor cured with a syrup stewed from wild roots.

The lad had an intense love for his grandmother. When she died, the family did not tell Billy for

two days. Heartbroken, he mourned at the casket, refusing to be moved. The second day after the

funeral Billy vanished; no searching party could locate him. Finally his pet dog picked the scent

through the snow, and, leading the posse to the cemetery, stopped where the lad lay thrown

across the grave, chill-bitten by a cold November wind, and sobbing so that the friends despaired

of his ever stopping. For weeks his life was at low ebb, but the healing tide finally came.

The wolf of poverty hovered constantly at the log cabin door, so that Sunday’s mother finally

decided to put her two boys in a nearby soldiers’ orphanage. She prayed and wept while the boys

slept on the train. When Billy said “goodbye” he never dreamed that for the last thirty years of

his mother’s life, which ended June 25, 1918, he would have the joy of providing a really decent

home for her. That last June morning when he called her to breakfast she had gone on to heaven

without stopping to kiss her boy “goodbye.”

Sunday’s first job after leaving the orphanage in his mid-teens was mopping a hotel which he

also served as barker, orating its advantages to incoming train arrivals. Three months of that was

enough. Then, learning that Iowa’s lieutenant governor needed a boy, he polished his shoes, had

his hair trimmed, and convinced Colonel John Scott’s wife that he, Billy Sunday, was the young

man qualified for the job.

Colonel and Mrs. Scott sent him to high school, where, after two years he became school janitor,

meanwhile continuing his odd jobs for the lieutenant governor.

His baseball career began with a local team in Marshall-town, Iowa, for which Sunday played

left field. It so happened that Pop Anson, captain of Chicago’s famous National league White

Sox (now the Cubs), spent his winters in Marshalltown.

When the topic turned to baseball, which was Anson’s usual diet, he found the townspeople

talking about Billy Sunday’s speed on the diamond and his ability to nab fly balls that nobody

else would even attempt catching.

Considering that Sunday could run three hundred yards in thirty-four seconds, it was no surprise

that he caught flies like some folks catch a cold. Cap Anson’s aunt, who lived in Marshalltown,

urged the sportsman to take Billy to Chicago for a trial. In the spring, accordingly, a telegram

summoned young Sunday for a Windy City tryout. Buying a new green suit for six dollars and

borrowing money for the trip, Billy met the captain.

On Sunday’s first day on the diamond, Anson set the lad to a foot race against Fred Pfeffer, crack

runner for the Chicago team. Sunday had no running shoes, so ran barefoot. He not only won the

race by fifteen feet, but won his way into the hearts of the players. Cap Anson tossed him a

twenty-dollar gold piece.

During his first few seasons, Sunday succeeded in batting so poorly that the team considered it a

total mistake when he actually did connect. He struck out the first thirteen times at the plate.

Thereafter he began to find his stride.

Sunday broke into professional baseball when its players were rough, profane and hard-drinking

fighters. He did not need much encouragement for profanity himself, nor was he adverse to wine

and beer. During the winter months he attended Northwestern University; during the summer he

whacked the horsehide. He proved a splendid base-runner and a brilliant fielder. Seldom faring

exceptionally in the batter’s box against professional pitchers, he nevertheless in one game got a

home run and a single against an outstanding twirler. He was at his best when he stole four bases

while Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics was catching.

Sunday’s later pulpit pre-eminence did not spin a halo about his previous athletic success; rather

his evangelistic success gained added glow from the days on the diamond, for he was known to

sports fans of his generation as the speediest base-runner and most daring base-stealer in

baseball. In his earlier days he took too many chances, and his judgment was not always sound.

But his control over the ball enabled him to throw straight and swiftly, and he was so fast on his

feet that more than one top-rate player threw wild in the effort to head him off. He could stretch

ordinary one-base hits into doubles without trouble to anyone but the opposing team, and he was

the first man to run the circuit of bases in fourteen seconds.

In 1886, when Sunday had been three years on the Chicago nine, he walked down State Street

one Sunday afternoon with some of the biggest names in baseball. (In those days they played no

Sunday games, for there would have been no crowds). The party entered a saloon, had a round of

drinks, then walked to the vacant lot at State and Van Buren Streets. Whenever Billy Sunday

passed that lot in later years, even when Siegel & Cooper’s big department store had been

erected over it, he took off his hat, bowed his head and thanked God for saving him. Forty years

after Sunday’s decision, a policeman saw him stop and close his eyes in the midst of a crowd. He

offered to call a wagon if the man felt sick. Billy Sunday introduced himself and held a one-man

street meeting.

When Sunday and his baseball associates reached State and Van Buren on that memorable day,

some men and women in a horse-drawn wagon were playing horns, flutes and slide trombones,

and were singing hymns he had heard in Sunday school and which his mother used to sing- in the

Iowa log cabin. The baseball crowd sat on the curbstone and listened. Suddenly a winsome,

square-faced Irishman arose. That was Harry Monroe. He told how he once passed counterfeit

money for a gang of criminals and how he had been converted at Pacific Garden Mission.

“Don’t you men want to hear the story,” said Monroe, as he stepped toward the curb, “of other

men who used to be dips, yeggs, burglars, second-story workers, and who today are respectable

and have fine families? Or women who were slaves to dope and drink, or harlots who sold their

womanhood in the red light districts here, and who are now married in happy homes? Come

down to the mission tonight at 100 East Van Buren and you’ll hear stories that will stir you, even

if you’ve never been inside a church, or if you’ve wandered far away from God and your

mother’s religion.”

Billy Sunday turned to the fellows at his side and said, “Boys, I’m saying goodbye to the old

life.” Some of the men chuckled, others laughed, others were serious. Some of them paid no

attention at all.

That night at the mission Sunday was fascinated by the testimonies of men who went from the

guttermost to the uppermost. Again and again he attended and one night he went forward and

publicly professed Christ as Saviour.

The night he went forward he was not drunk, despite the story to that effect. Unfortunately,

Sunday himself gave that story credence when, in relating his conversion experience, he declared

that he “knocked over several chairs getting to the front.”

Harry Monroe had given the message and Sunday was under tremendous conviction. Mother

Clarke came back to his side and said, putting her arm around Billy, “Young man, God loves

you. Jesus died for you, and He wants you to love Him and give your heart to Him.” The ball

player could no longer resist. He swung clumsily around the chairs, walked to the front and sat

down. Harry Monroe came to his side and they knelt for prayer.

The next three nights Billy Sunday never slept a wink. He dreaded the jibes of the ball team at

ten o’clock Wednesday morning practice and during the afternoon game. He trembled when he

walked out to the field. There was Mike Kelly, one of Chicago’s outstanding stars, coming

toward him. Mike was a Catholic, and Billy expected almost anything.

“Billy,” he said, “I’ve read in the papers what you’ve done. Religion isn’t my long suit. It’s a

long time since I’ve been to mass. But I won’t knock you, and if anyone does, I’ll knock him.”

Then came the rest of the team, all of them, to pat Billy on the back and wish him the best of

luck. They were at a loss for words, too, and Sunday felt as if a millstone had dropped from his

neck.

Billy Sunday became even a better baseball player. He always insisted that taking Christ as

Saviour will make a man better at whatever he does, providing it’s a decent job.

That afternoon the Chicago team was pitted against Detroit, one of the hardest hitting squads in

the country. The Detroiters could be behind nine to nothing at the start of the ninth, and yet push

over ten runs in the final inning; they had a reputation for redeeming themselves.

This day, Chicago eked out a narrow lead right to the last inning. The Chicago twirler, John

Clarkson, one of the greatest pitchers of the day, had worked his famous “zipper” ball, with an

illusory upshoot, overtime. Two Detroit batters went down in the ninth. Billy Sunday, playing

right field, called in, “One more, John, and they’re done!”

The next batter was Charlie Bennett, Detroit catcher, who hit right-handed and nine times out of

ten sailed the horsehide deep into right center field. Sunday was playing far back, and followed

five speedy tosses, while Bennett came through with two strikes and three balls. The Chicagoans

knew that Bennett couldn’t hit a high ball close to the body, but he could set a low ball off like

dynamite. Clarkson braced himself for a bullet-ball high and inside. His foot slipped. The ball

went low. The resultant crack of ball and bat echoed through the stands.

Over in right field Billy Sunday saw it whirling through the sky, far over his head. Like a bolt of

lightning he turned. Following the approximate course, he ran so fast he forgot he could do one

hundred yards in ten seconds flat. As he ran, he prayed, “Lord, I’m on the spot, and now I’m a

Christian. If you ever help me, please do it now.”

The grandstand and bleachers were wild with excitement and thunderous shouting. To the crowd

standing along the right field wall Sunday yelled, “Get out of the way!” Through the opening he

sped, stopped, stuck his hand into the clouds with a leap. His fingers closed over the ball. As he

landed, he lost balance and fell, but jumped up with the horsehide secure in his hand.

The crowd went almost insane. Pop bottles, hats, cushions, and practically everything else went

flying into the air. Tom Johnson, later mayor of Cleveland, threw his arms around Billy and

shoved a ten dollar bill into his hand. At the clubhouse the whole team gave him a cheer, took off

his uniform and dressed him up. Then the crowd rushed in, carrying him off on its shoulders. At

the gate, brown-eyed, black-haired Helen Thompson threw her arms around him and kissed him.

She was the Mrs. Sunday-to-be.

Not many days later when the Chicago team traveled to a St. Louis series, Sunday happened into

a second-hand book store and for thirty-five cents bought his first Bible. At the end of the

season he joined the Bible class of Chicago’s Central Y. M. C. A., back in the days—as Mrs.

Sunday still puts it—“when the Y had Bibles, not billiards.”

After Sunday’s conversion in 1886, he spent three additional years with the Chicago team. The

people in the stands as well as his teammates knew that he had a working religion. On Sundays

he gave Y. M. C. A. talks, for which he was in great demand, and the sports pages all alluded to

his church activity.

An apt Bible student, he often testified, gave a brief Bible message, and then an invitation. He

developed increasing ability as a personal worker. Whenever the team traveled around the

country, Sunday was booked for meetings in local churches or with Bible clubs eager to hear his

testimony.

When he left the Chicago team, it was to spend a year each with the Pittsburgh and Philadelphia

clubs, but it was not difficult to discern that his interest in full-time Christian service was

growing.

Five years after his conversion, Sunday obtained a release from the three-year contract with

Philadelphia in order to enter some form of Christian service. No sooner done than Jim Hart of

the Cincinnati team pushed a $3,500 contract under his eyes. It was a tremendous temptation,

especially when Billy’s baseball friends told him it was the opportunity of a lifetime. After all,

players are on the diamond only seven months of the year, and Hart was including the first

month’s $500 check in advance. That night Sunday prayed, not stopping until five o’clock the

next morning. He refused Hart’s offer.

Billy’s alternative, that of going into Y. M. C. A. work as a subordinate secretary at $83.33 per

month, which sometimes proved as much as six months’ overdue, seemed a great anticlimax to

his baseball friends. To Sunday, that decisive March of 1891 was one of the greatest parting of

the ways in his life.

~ end of chapter 6 ~

***